I've always been really interested in US History, and especially the Civil War. I think it's an inevitable side effect of having a father who is a buff (though my brother never developed any interest, so I guess it's not inevitable ;) ). I firmly believe that there's no way to understand where we are without understanding something about where we've been. I'm not talking about learning about unusual people and memorizing dates - neither individuals nor dates mean anything unless the context is known. There are a few defining moments in American history, but I would argue that the Civil War is either the most or the second most significant (I might be prepared to cede the #1 spot to the events surrounding the Revolution). The Civil War is so defining that the entire period before it is called the Antebellum Period (antebellum, as in, before the war). Shelby Foote, one of the great historians of the war, talks about how before the war, people talked about the United States as a plural, as in "The United States are..." But after the war, they talked about the US as a singular: "The United States is..." It forged us from a set of states with individual identity in to a nation that saw itself as unified, even as the divisions that caused the war lingered.

Collar for a slave (National Museum of the Civil War, Harrisburg PA):

A lot of things happened before the Civil War began that led to it's happening, and the war wasn't inevitable. However, fundamentally, the war was about slavery. It was about state rights only to the extent that the southern states denied the right of the Federal Government to interfere with slavery and slave property that was protected in the states. The state rights fallacy is easily dispelled: if the war was about states rights, the south would not have insisted on a fugitive slave law, because they would have had to acknowledge that it was in the rights of the northern states to pass whatever laws they wanted about slavery. But instead, the southern states insisted that the government provided positive, explicit protection for slavery, even as they denied the right of the government to legislate about slavery at all! Contradictory? Perhaps - but it's worth remember that there was never any such thing as a South - just like nowadays, views are nuanced and no one area all felt the same way about things. Leading up to 1860, a series of political and social battles paved the way to the war - battles that had they gone differently, had the combatants made different choices, could have resulted in history going very differently and might not have led to a Civil War. If the Compromise of 1850 doesn't overturn the Missouri Compromise, perhaps there is no war. If John C. Calhoun doesn't change his position on the constitutionality of federal interference with slavery, perhaps their is no war. However, we'll never know. The specific events don't matter so much as the common thread: all of the events involved slavery. But it's more than that: repeatedly during the 1830s, 1840s and 1850s, the actions taken by the South began to make it clear that in order to preserve the servitude of African Americans, they would need to infringe on the rights of whites. And thus it came to be that hundreds of thousands of people in the north who didn't care on bit whether the African Americans were slave or free came to care passionately about the importance of protecting their own freedoms, without interference from what they saw as an elitist slaveocracy. On the other side, the Southerners felt increasingly that they were being manipulated and controlled by a mob of Northern wage slaves and immigrants. Not a recipe for friendship!

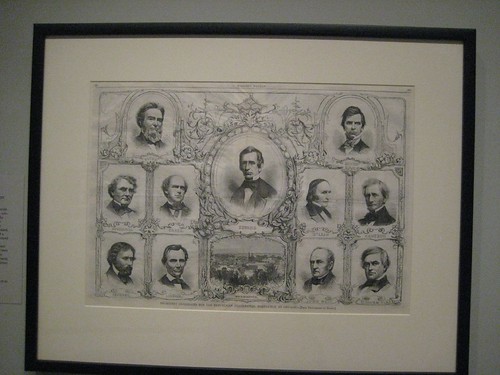

Nominees for the Republican Presidency (Smithsonian American Art Museum and National Portrait Gallery, Washington DC):

These contradictions, and everything that they represented, tore apart the only national party that had survived through to 1860, leading to a contested election with four nominees - a northern Democrat (Stephen Douglas), a southern Democrat (John Breckinridge), a Unionist (...er...something Bell) and a Republican (Abraham Lincoln). Can you even find Lincoln in the image just above? A few months before, he was hardly known at all. It's amazing what little events can shape history! The selection of a compromise candidate led to the election of a Republican even though there were states in the south that didn't cast a single vote for him. Had the Democratic party hadn't split, Stephen Douglas would have been elected, and the Civil War wouldn't have broken out. So why did it happen? After all, Lincoln vowed over and over again that though he personally felt that slavery was a moral wrong and that slaves should be manumitted and sent to Africa. The South didn't believe him, but how could that alone have driven them to secede?

The answer is, it couldn't. However, in the 19th century, elections were about more than just the office in question. Whoever won the election had it within his power to appoint his supporters to political (but not elected) offices. This spoils system was used to reward those who helped get you elected. So, if Joe the butcher, an influential Republican I've just made up, helped get Abraham Lincoln elected by encouraging his township to vote for Lincoln, Joe might be rewarded by being named the postmaster of his town. This is all well and nice when Joe lives in Illinois, but in the South, they knew that the Republican party was the anti-slavery party, and they knew that once Lincoln started appointing Republican's to offices in the South, it would be impossible to prevent the development of a local anti-slavery group. After all, not everyone in the South was pro-slavery, many were just conforming (for any number of reasons not worth going in to). Rather than let this happen, South Carolina worked up the nerve to secede, and was followed soon after by Georgia, Mississippi, Florida, Louisiana, Alabama, and Texas. But that wasn't war, yet.

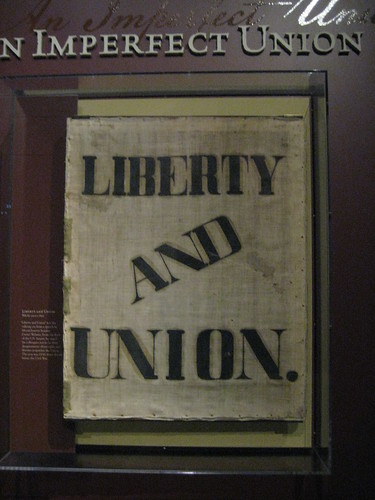

War Banner (Gettysburg National Military Park Museum):

Both sides started to mobilize. Southern states seized formerly national arms depots to arm their revolutionary militias. Forts held by soldiers loyal to the Federal government were ordered to surrender. Some did surrender. Some left. Some decided to join the rebellion. And some held out. A small contingent of troops under a Major Anderson, positioned at a fort called Sumter located at the mouth of Charleston Harbor, decided to stay, and soon became a key to the whole situation. The South Carolinian's insisted that they withdraw. Lincoln told them to stay. The fort was the property of the national government, after all. Militia under P.G.T Beauregard surrounded the fort, and rebellion - now called the Confederate - ships prevented goods from reaching the troops. Anderson considered surrendering. They were running out of food. Lincoln was walking a fine line with his policy. War was looking increasingly inevitable, but if the north were goaded in to firing the first shots it would change the entire international perception of the war. Relations between the two sides broke down rapidly, and finally the Confederates delivered an ultimatum: surrender Sumter by tomorrow or else! And Anderson wrote back and said, well, gimme a couple days, and if we don't get any food or reinforcements, we're going to have to leave! And the Southerners decided that wasn't good enough, so instead of letting Anderson evacuate on April 15th, which he surely would have, they opened fire on April 12th just at first light. The bombardment lasted 36 hours before the Anderson's men surrendered. The only casualty was a horse. As soon as the men of the North - the Union - fired upon the South, North Carolina, Virginia and Tennessee joined the Confederacy, and the course of events was set (at least to the extent that there would certainly be a war). Four years later, 650,000 men north and south would be dead.

So, those first shorts matter! Until that moment, there was still the chance that something else might happen. What if Beauregard's South Carolinians had let Anderson have his couple of days? What if Anderson hadn't bothered to hold Sumter at all? What if Lincoln had ordered the fort evacuated, or ordered it held at all hazards? Part of what makes history so fascinating is that at the moment that the men, women, and children involved made their decisions, they faced numerous options, and made choices for a whole range of reasons, and they didn't know what would happen. We look back, and we say, "that was inevitable," or "that was the critical moment," or "that didn't matter at all," but at the time, the parties involved didn't know which events mattered, they just did the best they could with what they knew and what was at end.

When Abraham Lincoln stood up to take the oath of office in March of 1861, he made an impassioned plea in his inaugural address: "We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearth-stone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature." We face a time now with a lot of sectional conflict, and every day I find myself hoping that we too will be guided by the better angels of our nature!

Okay, I'm done babbling history. Here's the plan! I've been setting aside the dates over the next few years when the 150th anniversaries of the major battles will take place. I'll do a full photograph post related to each one, and babble some more about history (sorry, everyone, but it's my blog, ha!). The first big anniversary is Bull Run, on July 21st of this year, but I've never been there before, so no pictures to share (but I'm going for the whole week around the battle). Here are some previews of what else is to come! :)

Shiloh (TN. Anniversary will be April 6th and 7th of next year):

Antietam (MD. Anniversary will be September 17th of next year):

Fredericksburg (VA. Anniversary will be December 11th and 12th of next year):

Gettysburg (PA. Anniversary will be on July 1st - 3rd of 2013):

Chickamauga (GA. Anniversary will be September 19th - 20th of 2013):

...and there will be others! (including some I've not been to! And others that I don't seem to have any good photographs of! :) )

Anyway, I've let this go on long enough, but I can't resist signing off with a shot of my personal hero.

I just can't say I think William T. Sherman is awesome anywhere south of the Mason Dixon line, or I'll face the consequences. :)

No comments:

Post a Comment